Interview by: Mark Lacey

When Russell Gilbrook joined Uriah Heep as their new drummer in 2007, replacing the legendary Lee Kerslake, whose own career had been cut short through ill health, he brought a renewed energy and his unique style to the band. Almost 20 years’ later, Uriah Heep are at the peak of their powers; their latest album ‘Colour & Chaos’ is riding high on the rock charts, and the band have just begun an extensive global tour, beginning with UK dates alongside fellow metal stalwarts, Saxon and Judas Priest. However, despite being known as one of the most solid, and exciting rock drummers of his generation, Russell’s musical beginnings will enlighten and surprise many.

Russell discusses a vibrant and diverse musical career

MGM: Most people will be familiar with you through your work with Uriah Heep. You joined them in 2007, but your musical career goes back a long way before that, doesn’t it?

Russell: Apparently, I was crawling, tapping my feet, and bashing plastic bowls with spoons and stuff, and I was about three years old when my mum and dad thought, I think we might have a drummer. I had my first lesson when I was four with a really old big band drummer called Georgie Scott you used to live in Leytonstone. I took to the drums like a duck to water, and I stayed with him till I was six and he said, “Look, you’re playing better than I am now. I can’t take you to the next level. There’s this up-and-coming drum teacher in Hornchurch called Bob Armstrong. You need to go to him”. I went to Bob from the age of six to fourteen, and at my last lesson (that I cried at), he turned around and said, this is your last lesson. I couldn’t believe it. I used to look forward to every single lesson with Bob. He said, “I can’t teach you anymore because you’ll end up being a clone of me. You need to go and develop what I taught you, listen more, take on every gig under the sun, get experience under your belt, and be a musician”. And that’s what I ended up doing. From then, I was Bob’s number one drum dep. I did Jesus Christ Superstar when I was twelve, and The Wiz. I actually ended up doing Andy Capp. That’s when I first met Alan Price, and I joined Alan Price when I was eighteen, and did five and a half years with him. With that same agent, I joined Chris Barber’s jazz and blues band, and that’s when all my dad’s old records came out. I had to learn how to play like Baby Dodds and really get my swing thing together. From Bob and my dad, I was taught jazz right from the beginning. I was playing in jazz bands when I was six or seven, sitting in with them, learning how to play jazz properly. I met the great Ed Thigpen at a big festival in Germany, and he turned around and said, “Hey man, for a white guy, you really know how to swing”. I thought, bloody hell, that’s amazing to come from someone like that.

Alan Price had a great keyboard player called David Rose, who was in with RCA records, and that’s how I ended up doing Van Morrison, Lonnie Donegan, and all pop stuff; ‘5 Star’ and ‘John Farnham’ stuff. I recorded with John Farnham for RCA Records. He didn’t do any touring in Europe. He used to say to us that the Australian musicians didn’t like leaving Australia, so as a band we said to him, “Well, we’ll do it. If you come to Europe and you want to do some touring, we’ll be the band for you”. But it never materialised. I did the Montreal Rock Festival with John Farnham in 1987, and that’s when I got my first cymbal deal with Sabian. But what an amazing singer. Jesus Christ. That guy’s vocals are outstanding; probably the best I’ve ever heard in my life by anybody.

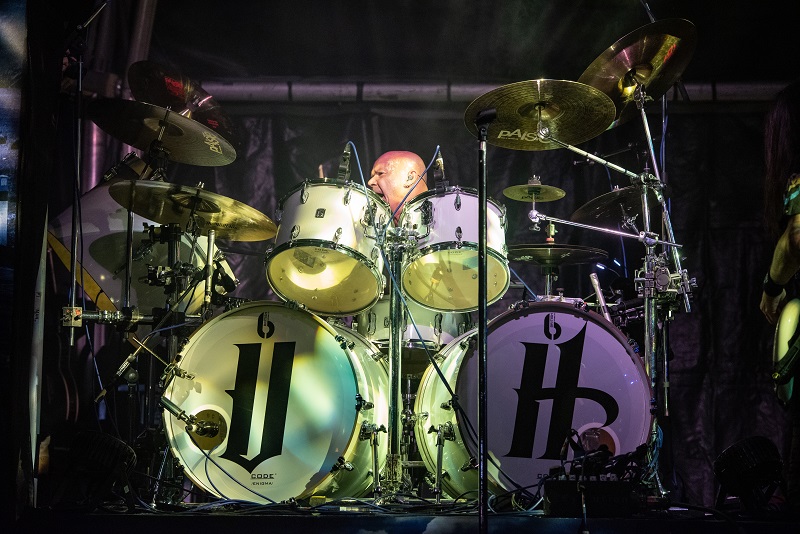

Photo Credit: Richard Stow

MGM: Your parents got you drum lessons at a really early age, long before you would have heard much recorded music. You’ve described the influence of your drum teacher, but who else inspired you in those early days?

Russell: Well, there wasn’t anyone, because from a kid, I idolised my drum teacher. When he used to do local jazz gigs and jazz-funk gigs and stuff like that, I used to tag along and be his little roadie. I could only carry a snare drum because I wasn’t strong enough, but I used to sit right by him, just watching him play. I never really had any influences outside of my drum teacher, Bob Armstrong, and I was always gigging, and earning £30 a week from the age of six. I didn’t really go down the road of latching onto drummers, really. I was too young. It wasn’t really until Spectrum came out with Billy Cobham, and that just blew my mind. He really took a hold on things. Even when I got older, I made a conscious effort that I didn’t want to latch onto any drummers. I remember Bob Armstrong saying, “You’re going to be a clone of me. I don’t want you to be that”. Well, I don’t want to be a clone of anybody else. I admired so many other players for so many different reasons but I never really had a single inspiration because I didn’t want to end up being influenced too much by them. I used to love Gene Krupa’s charisma. I loved the way Louis Belson swung, and I loved the ferociousness of Buddy Rich. And Steve Jordan; what a groove. It’s just outrageous that you can play so simple. And yet to me, that’s why I play drums. Everyone can be flash if you practise hard enough and get a few chops together. But you never once get told, can you play with flash chops. You get told about timing and groove and expression, and being a nice guy. They’re the things that contribute to everything. There’s so many players I like for different reasons, and I can’t make one better than the other. It’s an impossibility.

MGM: When you have the time, you still teach yourself, don’t you? Do you follow the same principles that Bob Armstrong did with you?

Russell: No, sorry. I’m a bit of a controversial drummer. Always have been. I don’t believe in rudiments. And that’s through my own experiences. I’ve spoken to several drummers about it, Kenny Aronoff, Dave Weckl, all these guys. And if you speak to them, they don’t do 47 rudiments either. I did the 26. When I was learning to play for Bob Armstrong, there was only the American 26 rudiments. There wasn’t anymore. And now they’ve invented rudiments left, right and centre. That’s fine if you play in a pipe band or a marching band, because you need to have the variety of phrases. Dave Weckl says he only uses five. Kenny Aronoff says he only uses about four or five. I believe that there’s only two really; singles and doubles. At the end of the day, a paradiddle is a combination of two singles and a double. The five-stroke roll is two doubles at a single. A flam is a quiet single and a loud single. And you can go on through all of the rudiments and break them down into two main ingredients.

Most people either struggle with a double stroke, or they struggle with accents to ghost notes and controlling the difference. That’s what a paradiddle is. I started focusing when I was about 18 on the two rudiments, just doing 16th notes at whatever tempo, and letting my hands be free to move from singles to doubles. And if my left hand fell on the one, which most people don’t like, I learned to accept it and be comfortable with it. I got more out of my drumming by focusing on my singles and doubles being really good, and because my doubles are so good, I don’t need to practice a seven-stroke roll. So, I tend to teach that method. And the reason I do, is I want to give people something simple. If I give you two things to learn, it’s far better than if I give you 200 things; you can get more out of it, because we all know repetition is the way in which you build up solid technique properly. So, I’m a bit more of a controversial teacher. With the world of social media now, I’ve seen people practicing a really cool thing on the drums. To me, it’s a very good, independent exercise, but it has no bearing on drumming whatsoever because you wouldn’t play that in a real gigging situation. I like to focus on the phrases and the technicalities that I’m using on World tours in 64 countries, and observing Simon Phillips, and observing Dave Lombardo, and observing all these other guys, and having a drink with them after. What I’m seeing is, they play what I play. We play it differently, but we’re still playing very similar phrases within a song situation. That requires an amount of technique. And it’s not all of this other stuff; the intricate, hard, independent stuff and flashy drum fills that people have worked out, that sounds amazing, but you get fired if you played it with the band. You just wouldn’t play it in the band.

MGM: You joined Uriah Heep in 2007. How did that call come about? And how aware were you of the band before you were approached?

Russell: I wasn’t as aware as I thought I was when I heard the songs. I didn’t associate the songs with the band. I was doing a lot of clinics at the time for Mapex drums up and down the country. One of those was at REpercussion, in Hull, and that’s where the late Trevor Bolder, the bass player with Uriah Heep, was living. We’d have 200-300 people, and it was always a fantastic night, but every time I went there, Trev was away on tour with Heep. Phil always used to say to Trev, “You’ve got to come and see Russ play”. This one particular time he came and saw me play. Afterwards he said, “Your drumming was fantastic, I really enjoyed that. What are you doing after? Have you got a rush home? If not, come around my house, let’s have a chat and some lunch”. So, I did and we become mates. But it wasn’t until about seven years later that he called me up and said, “Poor Lee’s health isn’t very good and we’ve just signed a recording contract, we got an 18 month world tour, would you be up for it”. I’d been doing Helen Shapiro, Alan Price and Chris Barber, I thought not another old has-been band. I couldn’t take it anymore. When I put the phone down, I did some more research, of course I was wrong; a classic legendary band, and I loved it. I called him back, I said, yep, I’ll be well up for it. He said, but the only problem is the management are doing auditions. I wasn’t bothered about that, I’m Russell Gilbrook, I’m going to be Russell Gilbrook, and you either like it or you don’t. So, it’s 240 drummers and a lot of chancers and it whittled down to the last 40 at Terminal studios.

I was very clever because I wangled the last audition on my drum kit. I pretended that I could do one, and then I rung back and said, oh no, I can’t make that. Can we do next Monday? Oh, sorry about that. I forgot I got a dentist appointment. I managed to wangle the last Friday and they had a kit up there. I said, “I’ll destroy that in ten minutes. Can I bring my own kit up? I’m the last audition, so it doesn’t make any difference”. So, I wangled the last audition with my kit. There were five songs to learn that covered the spectrum of the technique, including the double handed shuffle, which even today a lot of drummers can’t play, but Lee played fantastically well. So, there were five songs. I get called in, I’m setting up, of course I know Trevor, having a good old chat. I’m thinking really confidently. And just before that, I did think, are they going to want a Lee Kerslake clone, because they’re used to him for 37 years. No, this is my time. I’m going to be Russell Gilbrook. They like it or they don’t. So, I’m setting up, we’re having fun, having a chat. And then they said, so you’ve learned the five songs then? And I stopped and went, what? Have you learned the five songs? I went, no. And their whole face dropped because they’d had a nightmare for two weeks. I said, I’ve learned the whole live set and we could do the gig tomorrow. And suddenly they were like, what!!! So I’d completely prepared myself and learned the whole live set. We did the audition. I was me, obviously. I played double bass drum, Lee didn’t. I thought it added a bit of my personality and a little bit more drive, and a bit more of an engine room. They seemed to like it. I came off stage, spoke to Mick after ten minutes. I said, hang on a minute, you’re talking to me like I’ve got the gig. He said, you have. Now we’re going to go around the pub and get pissed. And that’s what happened.

MGM: Did you imagine at the time that would have ended up being what is now an almost 20 year tenure?

Russell: I’ll tell you what, when you do the amount of touring that we do, the years go as fast as a month. It’s outrageous.

MGM: Mick Box is like the Peter Pan of rock, isn’t he? He’s been doing this almost 55 years. Why do you think Uriah Heep has been able to sustain through that length of time?

Russell: It’s the songs. I think the advantage that those bands had from the 60s coming out into the 70s, is that they started everything, and everybody else has been influenced by those starters. You can survive right through the decades, a bit like the classical, Mozart, Beethoven, if you like. But the songs; Heep had so many great songs. Obviously, they had some bad songs, and some bad albums too, like all bands. But basically, the songs have been so good that they stood the test of time for so long. It’s seen them right the way through. And the younger generation want to know where it all started, and delve back into mum and dad’s albums. They get just as excited when they hear where it all came from.

MGM: The tour started on 11th March, and you’re playing a number of dates in the UK with Saxon and Judas Priest, after which you’re going to Europe. How much have you been looking forward to these shows?

Russell: We’ve had a very lenient three years, really, and I just can’t wait to get my teeth stuck into it. They’re good friends of ours, Saxon and Priest, so we might have the occasional fun night. But, we’re playing arenas, it’s three great bands, and all British. It’s just very exciting, not only for the fans, but for us. We haven’t had a chance to celebrate our ‘Chaos & colour’ album, which came out just over a year ago now. So, we’ve got two new songs from it. Saxon have got a new album out. Priest got a new album out. So, it’s very exciting times all round for everybody.

MGM: You played some dates just before Christmas around South America, and it looks like the majority of the songs performed were from those really early albums. There were a couple of the newer ones from ‘Living the dream’, but most of the set was from that 1970 through to 1974 period. What are your plans for these shows?

Russell: The good thing about Uriah Heep is it’s such a crossover band. They’ve got their nice acoustic, melodic songs; they’ve got the heavy songs, they’ve got the proggy side, so we can fit into different areas. But obviously, with Saxon and Priest, we’re going for a much heavier set. They’ll be two from ‘Chaos & Colour’. I think we’re going to try and put in a track from ‘Abominog’, and when we go to America, we’ll tweak the set again, as obviously ‘Sweet Lorraine’ was really big in America, as was ‘Stealin’.

MGM: After you do this first run with Priest, you’re off to the US with Saxon, and you’ll be playing another 31 dates, and then you come back and you do the festivals. That sounds relentless. How do you prepare yourself mentally and physically for that?

Russell: Well, we’re all slightly different. I’ve never really had an issue. I really embrace it. I’ve got called ‘the robot’ quite a few times by support bands when we’ve done long tours, just because it takes me two days to settle into my gig fitness level, and once I’m there I could do 50 days and I don’t get tired at all. I don’t know why. I think I’m lucky with my body makeup. But, I can’t play drunk, so you’ll never see me do that. I like to enjoy a bottle of red with a nice meal on a day off to treat myself, but I will never have anything compromising my playing. Because I play so vigorously, it obviously aids my fitness level. I’ve always treated every gig like it’s the first and last. Because if I was going to play my first gig, how exciting would that be? And if I knew it was going to be my last gig, I’d want to play the best and have it be the happiest gig ever. So, I can’t get bored doing a gig. I never get bored playing the same songs, or the same set. I approach them slightly different, I feel the audience slightly different, the room, the sound in my in-ears. I’ll try and dig in a bit more of a groove, or throw in more of an energetic fill to try and spark some inspiration to the bass player, or the keyboard player, or Mick, or whatever. I’ll always do that on every gig. That keeps it exciting for me. The fans pay money, they deserve the best show and I want to give them the best show.

MGM: Does playing so many shows make you prone to injuries?

Russell: Some people are just unlucky with injuries, but certainly to help the prevention of them, I do 45 minutes of warming up and the difference to when I start, usually after about 20 minutes, the difference is chalk and cheese. It’s not a little bit, it’s massive. Because when you play hard and fast, your forearms and your wrists are going crazy. They’ve got to be so loose. The forearms have got to be so warm and ready, it’s just like doing a 100 metre sprint. So, I’m very conscientious of doing my 45 minutes of warm up, including stretching, and then I’m ready to go out the traps. And I do it every single gig, even in a pub gig, because it’s part of my routine.

MGM: It seems that the drumming community is pretty strong, and there’s great camaraderie and respect between players. You were recently involved in the Cozy Powell celebration show at Christmas, alongside Harry James, and many others. Paying tribute to drummers from the past is really important, and people like Cozy Powell, Ginger Baker and John Bonham are often celebrated. But which drummers do you see coming through the ranks that really excite you for the future?

Russell: Oh, that’s a tough one. I think the business has destroyed a percentage of that. If you go back to the likes of Cozy Powell, John Bonham, and Iain Paice, the technology hadn’t destroyed their identity as a player. The way in which they tuned, the way in which they hit the drums, the way in which they played, you can hear it. You can hear who it is. And technology has slowly stopped all that, with the way in which people do samples, or the way in which they do recordings, using pro tools, tidying this up, tidying that up. It slowly destroyed the identity of players. You can hear Simon Phillips play mainly because of his distinctive drum kit, and you can hear Stuart Copeland, but you hear a lot of rock bands now and certainly metal bands, and it could be any of them playing on any record. It’s such a shame, because you spend a lifetime to nurture how to play, and to be yourself, only to get quashed by technology. So, I think it’s very difficult. There’s some exciting players out there. Darby Todd’s doing very well. He’s a nice guy. He’s taken care of the way in which he plays. He’s a great musical thinker. He’s taken care of his technique. He’s involved in the bands where he’s making an impression. In the old days, I think playing was more important. Nowadays it’s about contacts, being a lovely guy and getting yourself out there. The phone doesn’t ring itself.

MGM: Uriah Heep are going to be on the road for quite some time over the coming months. Will that present an opportunity for you to start thinking about writing new material together?

Russell: No, we don’t usually do it on the road. It’s usually in our own time. That was the big advantage of COVID as we couldn’t do anything, so we might as well get our writing juices out. It gave a chance for everyone to write. First time in 17 years that I got four songs on the last album. I’ve always had ideas, but songwriting to me is about a connection with somebody. I can’t write songs on my own. I’ve got so many ideas that go in my head, but I need someone to bounce them off. I’ve got a great mate, Simon Pinto, who can play guitar and bass, and I was over at his studio for three months writing 20 songs for Heep, and four of ours got put on there. And so, the creative juices tend to work better in our downtime rather than on tour.

MGM: MyGlobalMind recently caught up with longtime Tank guitarist, Mick Tucker in advance of their shows in London and Houston, TX. Mick recently posted about a new project called ‘High Upon High’ which features you on the drums. What can you say about that project?

Russell: Well, it was originally a White Spirit project, and it developed. I first got asked when the White Spirit thing came about with Brian Howe singing. They found this album that wasn’t released. They wanted to make a tribute to him and wanted their favourite players on it, and Mick, Cliff, and Mal (Malcolm Pearson) wanted me on drums and Neil Murray on bass. We ended up doing that album, and from that album I was going to get involved in the Tank stuff. I’ve been so busy with Heep, I couldn’t do it, and then with ‘White spirit’, Mel decided he didn’t want to do it anymore. So, it was like, OK, we need to get different personnel in, change the name, but keep the project going. So that’s what’s happening. It’s an ongoing development at the moment. Hopefully we’ll get stuck in when I get a bit more time. I hope it gets enough of a bite from the album that we do to warrant some live dates. It’ll be nice to do. I love doing loads of different bits and pieces with other artists. It’s great for your creativity.

http://www.uriah-heep.com/newa/live2007bit.php/