Interview by Mark Lacey

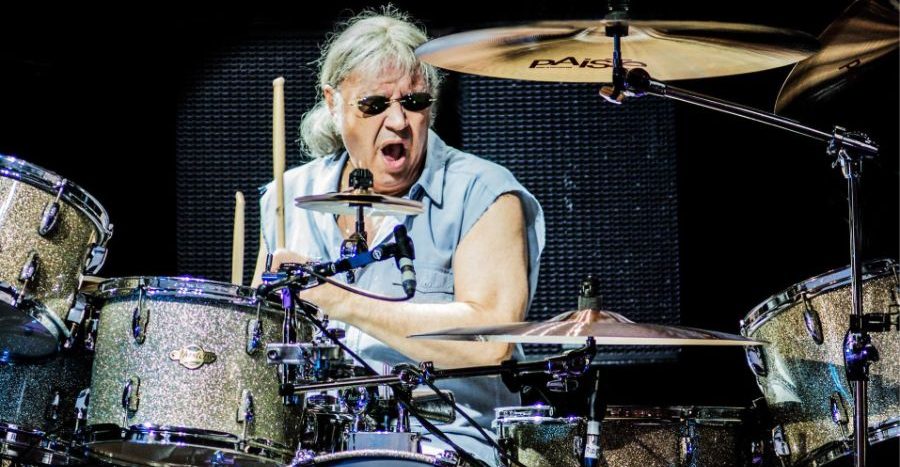

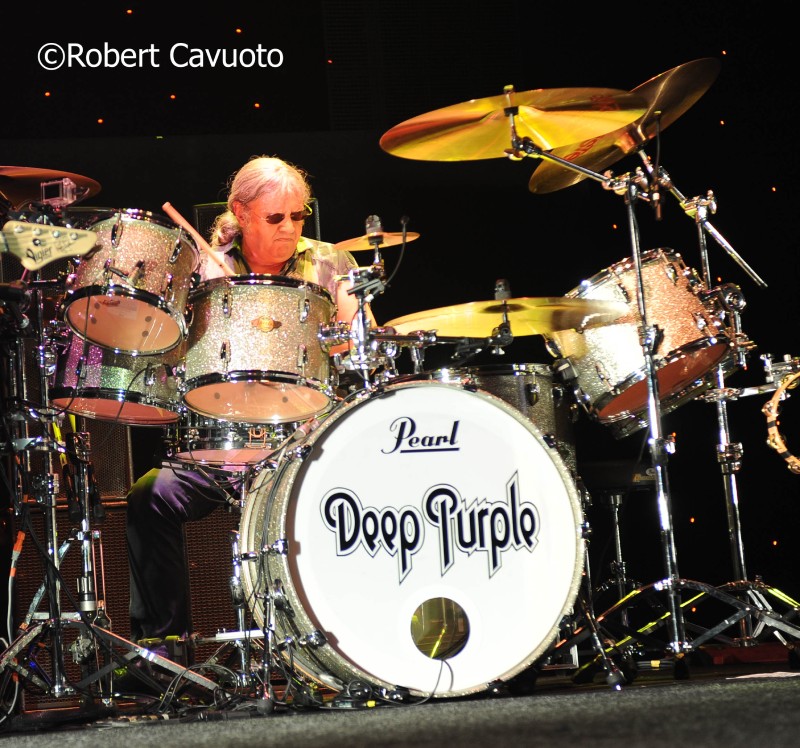

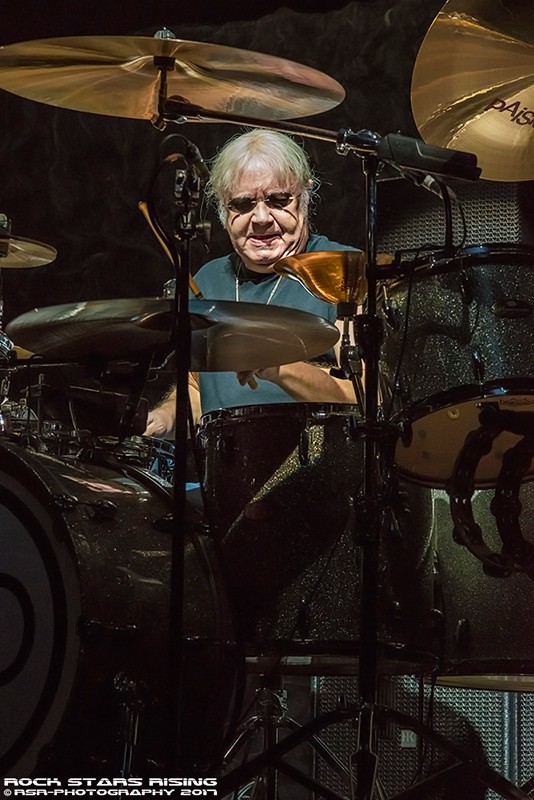

When Ian Paice tagged along with his friend and fellow Maze band member, Rod Evans, to give support during his vocal audition for a new band, the stars aligned. That meeting would also see Ian enlisted, alongside Rod, into what would become Deep Purple, and kickstarted a career with the band that has now lasted 56 years. Despite multiple line-up changes throughout those years, Ian remains the only member of Deep Purple to have served in every line-up, and has played on every album and at every live appearance. His unique style, boundless energy, and spectacular live performances have seen him recognised with the band through the Rock N Roll Hall of Fame, but also by fans and his peers as one of rock music’s greatest musical innovators. Ian talked to MyGlobalMind.com in advance of Deep Purple’s extensive world tour through 2024.

“I don’t think anybody who’s in a band thinks that it will still be there five years later. That’s not really the way it works. Even the Beatles, from the moment people knew about them until they folded, it was six years. It’s generally not a lifespan that goes on into decades. I think the only one that are outlasting us so far are the Stones. They’ve been out there a couple of years longer than we have”.

MGM: You got your first drum kit at the age of 15, which would probably be considered to be quite late, but you went from getting your first drum kit, to going into being a professional player very quickly. What are your memories of hearing music for the first time, getting into music and realising that drumming was something that you wanted to do?

Ian: I suppose it all started when I was about 11, maybe 12 years old, and I just got hooked on looking at drummers. I used to see these old black and white Hollywood bio pics where there’d be a big band playing from the ’30s and ’40s, or they’d be there as a featured five-minute section of the movie. There was one guy, Gene Krupa, and he just looked mesmeric. So, before I wanted to be a drummer, I wanted to look like him. I got a pair of old knitting needles and I started trying to copy what I saw his hands doing on the TV screen. TVs were about nine inches in those days. I would sit on the armchair of the sofa and play with the knit needles on the furniture. Then I realised that I understood why the notation was doing what it was, why one hand was doing this and why the other hand was doing that. So, it automatically made sense to me.

I’ve spoken to some other players, not just drummers, but musicians who have, let’s say, had that advantage from nature, where they understood the instrument almost immediately. I carried on like that building drums out of our biscuit tins and big bits of Sellotape stretched across the top and with plasticine underneath to make a snare drum sound. It didn’t sound like it, but it was good to me anyway. My dad saw that this wasn’t going away, and so on my 15th birthday, he bought me my first drum kit. A piece of rubbish, but it was a start. And my first gigs were with him. He was a really good piano player, and he had a little trio, sometimes a quartet, and he’d do dinner dances on Saturday nights. Over the Christmas period, he’d make a fortune. So that’s how it started. I played the odd gig with him with waltzes and quick steps and foxtrots and military two-steps and stuff like that. But like any kid, I was 15 and a half by then, a little local band got up together and I took it on from there.

When you are in a band that’s working, even the lowest possible level, you see other people playing. They could be absolutely crap, but they might have one thing, and you go, I like that, and you bring that into your repertoire. If you’re playing two or three gigs a week, which we were, as semi-pros those days, you saw lots of guys playing. So, you got this little bit from there and that little bit from there. And all of a sudden, you found you’ve got a bunch of things you can do, which are now your own, and it goes on from there.

MGM: Did you take drum lessons when you were a youngster, Ian, or did you find your own way?

Ian: Well, no. I lived out in Bicester then, near Oxford, and there was nobody there who taught anything like drums. Quite honestly, within six months, I was the best guy in the area so if anybody was going to teach, it’d be me. But in those days, you could see lots of people play. Sometimes they were very good and you could learn a lot. Sometimes they weren’t very good, but they’d have one or two things which connected with you. And you take it and you bring it into what you do. It’s very hard for kids to do that today because they just don’t see enough different people playing. The ones that are playing now, as good as they can be, and they are some great players out there, it’s all very same-y because everybody’s learning from the same book. We had no book to learn from. We had what inspired us. Which drummers did we like? What sound did we like? And we tried to emulate that. Kids don’t get a chance; they might get two gigs a month.

MGM: Russell Gilbrook from Uriah Heep recently spoke to MGM, and he highlighted his conversations with other drummers about technique and rudiments. He only really concentrates on two; singles and doubles and combinations of. He also spoke passionately about how technology in particular has really killed off a lot of the character between drummers, leading to a lot of recorded drumming sounding the same. What’s your view?

Ian: I completely agree with what Russell said. I use about five or six rudiments; singles, doubles, paradiddles, flams, five-stroke roll, seven-stroke roll. That’s about it. In what we’re doing, the rest of it is totally unimportant. You’re not going to use it. You can’t make it work in that style of music. So don’t waste your time. It’s nice to know them, and to use them just as a control exercise, so that when you tell your hands to do something, they do it. But how you’d ever use a flam-paradiddle in a rock and roll tune???

Regarding the technology; some of those magnificent records, and I’m not talking about going back to the jazz period, because those guys were totally free …. but when rock n roll started from the ’50s, ’60s into the 70s, drummers were totally free then. Some of those wonderful drum fills that happened, those moments that would never be created again by that player. They were there for that moment in time, how they felt, how the drums were, how it came out. That doesn’t happen anymore. This regimented digital recording makes it very difficult to do that. On the plus side, if you get it wrong, you don’t have to do the whole song again. You take that one bar where you’re screwed up and you do it again until you get it right. But it’s not the same, and it never will be the same again. The only time you get to see drummers playing freely now, and not all of them, is when you see a band live on stage. Even then, a lot of bands are playing to pre-determined clicks. They’re sometimes playing with an augmented percussive track. So that freedom isn’t there anymore. Quite honestly, what you hear today on the radio, you don’t need a Buddy Rich to play that. It’s basically just time. Even the fills are square because the click’s going, and it’s so hard to break away from it. Even though we live in the click era, I still try to play some fills where it might not work two or three times, but I’ll get it there somewhere and it won’t sound like a click. That’s the important thing. When you start doubling up and quadrupling up notes, the possibility of going out with a click, it’s exponential. But if you can get two or three of them on a record, it makes it sound like there’s still a human being doing it and not some bloody awful piece of hardware.

MGM: You play left-handed. Did you always play that way around, or did you experiment right handed first?

Ian: All drummers that can play are somewhat ambidextrous, or else you couldn’t do it. That means you do some things with your weaker hand. If I throw a ball, I throw it in my left hand. If I pick up a cricket bat, I’d hold it right-handed. So, there is a crossover there. But when it came to holding a pair of drumsticks and making time, it was always the left was always the dominant leading hand, as was my left foot. So, there was no thought about it. When I got my first kit, I had to turn it the other way around. I set it up the way it looked on the box and everything was in the wrong place. So, it was difficult. I remember when I got my first really good kit, when I was about 17, I got a Ringo Star kit; a Black Oyster Ludwig. It cost a fortune in those days, and I ordered it with a left-hand configuration because the mount only came on one side of the bass drum. I thought, well, it’ll be my special kit. I got the kit after about six months, but what they’d done is they’d taken the mount off, and drilled some more holes in, put it on the other side and filled the holes in. So, my specially ordered kit really wasn’t that special after all.

MGM: Once you got your first proper kit, you were out playing professionally pretty much immediately. You played with your dad’s band, and then you worked with The Shindigs, before going on to play with the Maze, which also featured future early Deep Purple member, Rod Evans. That band was also the first time you recorded professionally, and released a couple of singles.

Ian: When I joined the Maze, I was 17. I was technically professional then. That’s where I got all my money from. I think we managed to scrape about £15 a week each. I was earning that before I was in a professional band. All it meant was I didn’t get up in the morning; if I got home at 3am from a gig, I could lie in. There wasn’t much difference other than you played every night. When you played two or three nights a week, you saw lots of guys. When you played six, seven nights a week, you saw everything. You saw really good players, and that accelerates your possibility to get better, because you’re seeing. It’s no good somebody just telling you, you’ve got to see how it happens. You’re got to see why it happens. Why did he do that? Why didn’t he play so hard there? Ah; he didn’t need to. Why did he make a statement here? Because he needed to. Although some of it is second nature, a lot of it isn’t. A lot of it is actually listening to what you’re playing, and what is the correct thing for the drummer to do here. You learn that by watching guys who are that much further along the road than you are. That was the important thing with the Maze in those two years.

MGM: In those early days, you went from The Shindigs to doing the Maze, and you did quite a few sessions. Then, pretty early on, you ended up going along to a studio audition with Rod Evans, and that became the beginning of Deep Purple. Did that early part of your career feel planned, or was it just right place, right time?

Ian: I think it’s always right place, right time, and a great element of luck. I was playing very well for a kid of my age at the time, but I’m sure there were probably half a dozen really great drummers in there, who just weren’t there at the right time, right place. I think anybody who has achieved success in show business has to have three things. You’ve got to have talent. You can be lucky and be there for a year and disappear. You’ve got to have talent, but you need that fortune of being in the right place. And you need somebody to have seen you and to give you that break, because if that doesn’t come along, you just continue on. We worked out that in the mid-late 60s in London alone, there were probably 10,000 working bands. You work it out. Four people in a band, that’s 40,000 musicians. What percentage of those players actually carried on to where it became their life? Not because they didn’t want to, just because it didn’t happen. The percentage of people who did it, either had to be really great, really different, or just had that element of luck. So, the other two things went with it. I’m a great believer in that.

MGM: During that early period of time for Deep Purple, you were out touring within a couple of months of it forming, and then recorded three albums in the first year. That must have felt like a roller coaster. Did it feel different to the other projects that you’d done previously, and could you have ever foreseen that this journey would have lasted as long as it has?

Ian: I don’t think anybody who’s in a band thinks that it will still be there five years later. That’s not really the way it works. Even the Beatles, from the moment people knew about them until they folded, it was six years. It’s generally not a lifespan that goes on into decades. I think the only one that are outlasting us so far are the Stones. They’ve been out there a couple of years longer than we have. Every other band is not there in its majority; The Who are still doing what they do wonderfully well, but there’s only two out of four. Purple’s got three out of five of the formation of Purple that turned the world in love with them.

Obviously, Jon died 12 years ago now, so that’s the end of that road. Ritchie chose a different direction because he didn’t like what was going on with Purple at the time. He didn’t like the direction that it was going with Glenn and David in the band. It was getting too bluesy, and funky for him, and he just wanted to stick to the rock n roll direction. There’s nothing wrong with that at all. So, he moved himself out of it. What we have is the three remaining important people in the band, and that’s always allowed the spirit of the band to stay where it should be, even though the music changes and the different capabilities of the people involved are slightly different. That’s just the way it is. But back to those early days, I was a kid. All I wanted to do was what I was doing. When we started, we were getting £25 a week, which was a massive jump from £15, and we were having fun and going to places I never thought I’d ever see, and people were liking it. That went on for 18 months. Music was changing then, and we were changing with it. That first incarnation of Purple was a little too gentle. It was still a bit poppy, and it was down to two things. Rod, who’s a lovely singer, couldn’t go where music was going. His voice just wasn’t built that way. Nick Simper didn’t like what was happening, and his love was what had gone before. So, if you’re not happy, you can’t do it. But the change in personnel which came along with Ian and Roger; that allowed Jon, Ritchie and myself to take it to this next level; moving it out of poppy hard rock to really serious pounding music because we had a voice that could do it. We had songwriters in the band, which we didn’t have before. We used to have to use other people’s music. We could write a couple of things, but they were always album tracks. They weren’t the things that people listen to on the radio. But I was a kid enjoying every minute of it. If I could have done ten shows a week, I’d have done it.

MGM: That first period of time up to 1975 with Purple was amongst your most creative, producing ten albums. How much did the revolving line-up, and the Mark I/II/III, influence that creativity, but also keep it exciting for you and the other members of the band?

Ian: I wouldn’t say it was exciting. I would say it was devastating when we changed, not so much with the first line-up, but from the second line-up. Every time we had a situation where somebody left, or somebody was asked to leave, or whatever; it’s a terrible feeling. You wake up in the morning, you’re in an outfit which is providing you a great living, and you’re having fun. And in the afternoon, you don’t have that. You’ve got to take five steps backwards now. What do we do? Do we go bang, and just go in our own different direction? Do we try and make it work with another person? It’s really tough. I don’t believe anybody that goes through this enjoys it, and I don’t believe it helps you create new stuff. It helps you create different stuff, because the chemistry is always going to be different. You got a small nucleus of four or five members, it’s not like losing one of the second violinists in a symphony orchestra. So, I always found it very difficult and I hated it, because I knew the work involved to try and get it back to where we had it.

MGM: People will always want to hear the classic songs at every one of your concerts. It’s documented that you’ve performed ‘Smoke on the water’ live almost 2500 times, and you’ll have rehearsed it many thousands of times again. How do you manage to continue playing it with such energy and passion, rather than just going through the motions?

Ian: It’s very easy. It’s two things. A good song is always fun to play. Even though after many decades of doing it, it does become somewhat formularised. Over those years, as a drummer, you worked out what are the best drum fills for each part of the song. They might not be exactly the same, but they’re all related to each other. Whereas when something’s very new, you’re still trying to find that. So, you end up with what you think is the best solution possible, musically. But the other thing is the audience; it’s what they get from it. That is incredibly invigorating. You understand that 80 % of them bought that ticket to hear that song. It’s the reaction you get from them. If you are feeling a little lethargic one night, that takes it all away. We’ve got songs which are probably more musically demanding to play, and as a musician that’s nice, but the audience don’t react in the same way. If they’re good songs, they’re fun to play, so it doesn’t matter how many times you play them. They’re never exactly the same every night. The structure, of course, is the same, or else you wouldn’t know where the hell are you going to finish. But what you do inside it can just be a couple of different fills, a couple of different accents, maybe up two beats a minute, down two beats a minute, whatever. As long as it feels right, there is some flexibility in it. And a good song is a good song.

MGM: Throughout your career you’ve played with many other people from Whitesnake and Gary Moore, and you’ve done sessions with Paul McCartney and others. But Deep Purple seems to be your natural home. Do you feel that connection with the other projects that you’ve done, or does it feel completely different to you?

Ian: It’s not completely different because when people want to work with me, they want what I do. Now, within certain tolerances, I have to tailor what I do to the music being created. Even within Purple when Glenn Hughes joined the band; great bass player, but totally different to Roger Glover. There’s so much less space when Glenn’s working, because he plays more notes. So, the drummer has to play a few less. Playing with Roger gives me more freedom to fill in those holes that he’s left for me. So, that is different. And in Purple, I’ve had the opportunity to fill in those holes. Working with Gary was great fun, but it was Gary’s band, and Gary’s music. I wasn’t exactly a sideman; I was a junior partner in it. But you understand the rules. Of course, working with the wonderful Sir Paul, it’s him. It’s not about you at all. The band had me, they had Dave Gilmour, but it was all about him. No matter how big a star you think you are, it’s him. There is a level beyond you don’t get near. But that was great fun, too. But you understand you’re there to do the job. But it’s not like Purple. And it’s not that it’s better. It’s just where I’ve learned my trade and found a vehicle that people enjoy what the drummer’s doing. In a lot of places, that’s just not possible because the music doesn’t allow it. Chad Smith, a great friend of mine, he’s a wonderful drummer, and so much better than people think he is, because with the Chilli peppers, all he’s doing is creating beautiful feel, and time. It’s all wonderful 4/4 stuff, and he’s so good at it. When you give him a chance to flap around on the kit, he’s as good as anybody, but it’s not needed for what he does. Purple has given me the vehicle with different tunes, and different styles to allow people to take notice of the drummer, which isn’t always the easiest thing in the world to do.

MGM: Deep Purple have just announced some new shows. You’ll shortly be playing in Singapore, followed by dates through June to August in Europe, and then you’re back in the UK and Europe at the end of the year. You’ll be 76 by the time you play most of those shows. How do you prepare yourself physically and mentally for playing now? And how has that changed through your career?

Ian: Mentally, it’s not a problem. It’s part of my adult life, and it’s what I do. When you’re a kid, it’s simple. Somebody phones up and says, you’re going to America tomorrow. You go, OK, I’m going. Later on in life, you’ve got family, you’ve got other things that take time in your day. It’s a little more complex to get it all worked out. But it’s what I do. It’s how I provide a living for my family. I wouldn’t stop it until I have to, or until I can’t do it anymore. That clock keeps ticking and there’s nothing you can do about it. Physically, there’s certain things I did in my twenties, that I would find very difficult to do today. Sometimes for the sheer physicality of it, and sometimes I’ve forgotten how to do them. But I also do things now that I couldn’t do then. That’s an evolutionary thing. But as crazy as it looked when I was 20 and everybody thought I was belting everything too hard, everything was always in control. I never put my body beyond where it should be able to go. I look at myself playing today, there’s not a lot visually going on most of the time, but I’m developing the same power. And I’m not making my body go through things that it shouldn’t have to. Therefore, everything still works. Any little problems I’ve had in the last 10 years have nothing to do with drumming; they’re just to do with years.

MGM: You talked earlier about Jon Lord’s passing in 2010. More recently, Steve Morse had to bow out because of his wife’s illness, and she sadly also recently passed. You had your own brush with ill health almost about 8 years ago, where it was reported that you had a mini stroke. Of course, Deep Purple can’t go on forever, and you won’t want to do a Tommy Cooper and keel over on stage.

Ian: Well, you say that. A friend of mine, we lost a couple of years ago, the wonderful Gary Booker. When he did the first Sunflower Jam with us, he said, “I think I’m going to die on stage”. We said, well, what better place to die? He said, “Oh, there might be one better place”. With him being horizontal rather than vertical. As a drummer, there’s going to be a point where those muscles will suddenly say, I’ve had enough. Or mentally, you say, I’d like a little more time not to do it. But I don’t see any reason why, if, God willing, my health stays as good as it is. It ain’t perfect, but it’s pretty good for a youngster my age, I’ll keep on doing it. And even when I don’t think I can do it at this level anymore, I can definitely see a situation where I find a couple of like-minded friends and maybe play a couple of gigs in a pub on a Saturday night somewhere, just because I like playing drums. When you get the great benefit, and luck of major success, you do get tied into one style of doing things. Often, it’s a limited amount of tunes you can play. Whereas if you’re footloose and fancy free, you could play a Deep Purple tune. You could play a Duke Ellington tune. You can be Bob Dylan. You can do whatever you want. You can back a Sinatra band. Because you’re not locked into being the guy doing this, the Deep Purple drummer, the Led Zeppelin guitarist. That freedom, sometime in the future, may be very refreshing.

MGM: You referred to Sir Paul earlier. Obviously, Deep Purple had been recognised in the Rock N Roll Hall of Fame. Do you feel Deep Purple has got the wider acknowledgement and recognition that it deserves? And after drumming for almost 60 years why has no one tapped you on the shoulder and offered you an MBE or Knighthood yourself?

Ian: Personal recognition? It’s not something that I worry about or think about. With Purple, you have to understand that what it became, and still is, is a niche market. It’s not like being Elton John. It’s not like being Sir Paul. It’s not like being ABBA. It just isn’t. Your audience is always going to be slightly more limited. There are going to be people who love what you do, and people who hate what you do. Whereas if you’re in the middle, most people are going to like what you do if it’s good. So, it is a smaller audience that you’re trying to appeal to. But you’ve got to be honest about what you’re doing. If what you’re doing you believe is right for you, then you don’t worry about how many people it’s going to get to. At the end of the day, every kid who picks up an instrument, every guy goes onto stage to act, every dancer does it to please themselves. Whatever happens afterwards, you could be lucky and it becomes your life. You’ve got to have fun yourself all the way through it. Otherwise, you can’t do it.

https://deeppurple.com/pages/tours